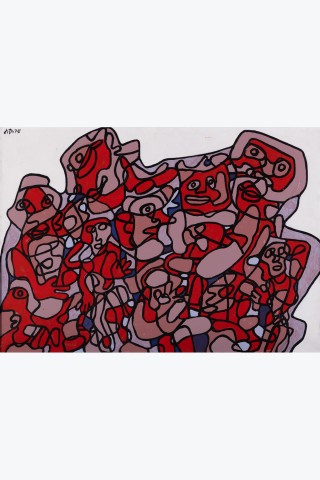

The figurative aspect seems to become clearer in the next series, entitled ‘Mondanités’, where human figures stand out against a plain background. But their physical identity and location are still unclear: they are intertwined, often on different scales, and are caught in an inextricable network of lines that seem to be in a frantic competition for life. Their graphic definition, moreover, is reduced to a minimum: a few elementary physiognomic indications, principally the eyes, represented frontally, fixed on us.

One of the most impressive forms of mimicry in animals, particularly insects, snakes and birds, is the ocelli, an amplified eye endowed with a hypnotic power that can paralyse or provoke panic. In humans, the hypnotic power of the gaze is further determined by fantasies linked to the anguish of interpersonal relationships. In this period of fundamental questioning of painting, oscillation, to which Dubuffet has always resorted as an elective treatment of surfaces, rediscovers its etymo-logical evidence. The eye is what sees and what can be seen; it is the centre of a chiasmus in which fundamental oppositions collide, notably that of subject and object. In this instance, then, the term ‘worldliness’ is to be understood not just in the everyday sense of being seen, but in the philosophical sense of being-in-the-world, linked to the function of appearing, and revealing one's allegiance to the scopic field.

Objectivity means forgetting or repressing the omni-vision to which the observer himself is subject. And Dubuffet's painting as a whole can be seen as a reminder of the parade nature of anything that claims to Be. So it rejects perspective, volume, local colour - in short, anything that might suggest a substantial core, an identity, a permanence, a location. Its main aim is to betray the essentially specular nature of objectivity.

Its paradigm is the eye, which evades any assignment and reverses the relationship between the seeing and the visible (Aloïse, who obsessively drowned her gaze in a blue colour of infinity, experienced psychically what Dubuffet experienced philosophically - but is the distinction still relevant?) And so the eye returns, like Cain's, to haunt the painting, which was supposed to consecrate the removal of the gaze, since it was made to be seen. Here, the voyeuristic relationship is unexpectedly reversed, as the painting looks down on us like an indefinitely multiplied gaze, reminding us that our vision is embedded in the flesh of the world, that ‘it is taken or made from the midst of things’ (Merleau-Ponty).

Michel Thévoz, ‘Crayonnages, Récits, Conjectures, Parachiffres, Mondanités, Lieux abrégés’, September 1974-March 1976, In Dubuffet, Éditions Skira, Genève, 1986, p. 47