All the works (lot 93 to lot 102 inclusive) were produced for the exhibition held at Galerie Jousse in Paris in association with Philippe Jousse between October 12 and November 18, 2017.

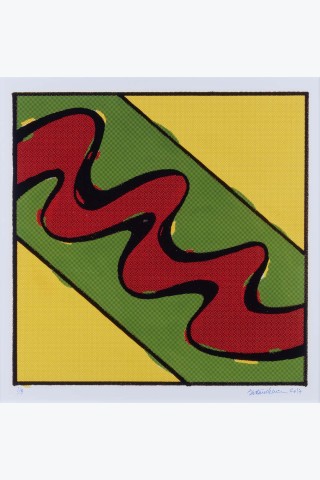

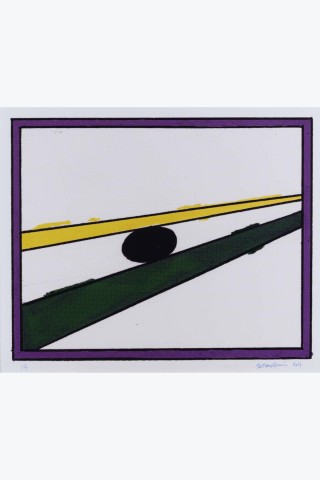

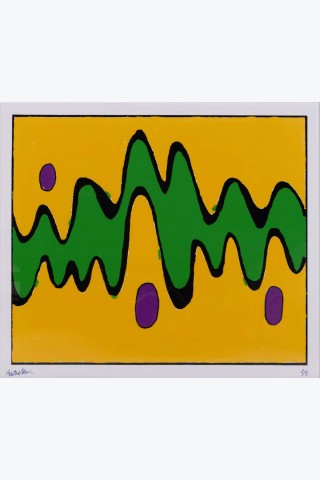

Bertrand Lavier's furniture paintings have always played, with humour and rigour, with the formal registrations and oppositions that structure the art world. He has never ceased to blur the boundaries between painting and sculpture, sculpture and object... The exhibition at Galerie Jousse, initiated and diligently organised by Serge Aboukrat and Philippe Jousse, takes things a step further by ostensibly confronting sculpture and furniture. Furniture by Prouvé, Paulin and Le Corbusier is set against the Walt Disney Productions series inaugurated by Bertrand Lavier in 1984. This series is literally based on a comic strip by Walt Disney published in the Journal de Mickey under the French title Traits très abstraits, which recounts the adventures of Minnie and Mickey at the Museum of Modern Art. By isolating the paintings and sculptures that form the backdrop to the narrative, and then enlarging them to the format assumed, Lavier creates a short circuit, giving the work the status of a work of art, something that had hitherto been little more than backdrop and fiction.

The photographic paintings and sculptures created from this comic strip now wander in an undecidable space, retaining the form of their original territory while having left it. In this sense, Walt Disney Productions is not an ironic commentary on modern art as told to children, but a reminder, as the artist remarks, that ‘it is the virtual world that allows us to approach reality more deeply’. By including this series in an exhibition of furniture that is emblematic of modernism, Bertrand Lavier is distorting the relationship between object and setting. Ever since Matisse, the relationship between background and figure has haunted Western painting. Abstract painting, however sublime it may claim to be, is also part of a form of décor (didn't the aesthetic avant-garde of the early twentieth century want to abolish the boundaries between art and life?) What distinguishes a minimal sculpture from a piece of furniture today?

What distinguishes minimal painting from wallpaper? What makes a setting? What serves as a showcase or a backdrop? Bertrand Lavier's photographs or the furniture on display? The photographs are artefacts, the furniture ‘real objects’. Yet when these two elements are compared, the objects become fiction and the photographs become verisimilitude. The furniture painting that Marcel Duchamp dreamed up for his daughter Yo Savy's works, a nod to Erik Satie's furniture music (Carrelage phoniqet Tapisserie en fer forgé, 1917), finds here a droll form of fulfilment.

Bernard Marcadé